By Mike Hudson;

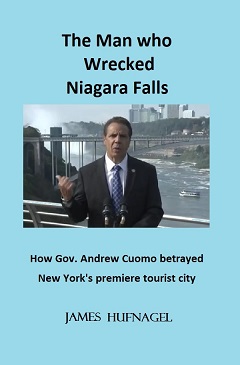

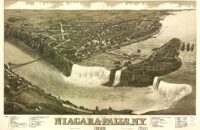

In the rush to placate the Seneca Nation of Indians during the casino cash dispute that dragged on for four years starting in 2009, Gov. Andrew Cuomo unilaterally granted a 10-year extension to the compact that allows the tribe to operate casinos in Niagara Falls, Buffalo and Salamanca.

He forgot one thing though. The original compact, signed in 2002, only calls for the tribe to pay the state 25 percent of the casinos’ slot machine revenue for 14 years. Those 14 years are now up, and there is no language in the extension that requires the Senecas to keep paying.

Nearly two months ago, Seneca President Todd Gates quietly announced that the casino cash flow would come to an end. The most recent payment, sent on March 31, would be the “final” one, Seneca officials said.

Since then there have been no substantive talks between the Senecas and Albany and there is little doubt based on both the 2002 compact and the 2013 extension document that they would win in court if the state tried to pursue a case against them.

That’s bad news for Niagara Falls, no matter how you look at it. The city has received as much as $21 million a year in casino revenue, although that number has plummeted to around $16.5 million as the region has become saturated with casinos.

Three new casinos open have opened since 2013 in central and western New York and the Southern Tier, and another one is planned near Syracuse by the Oneida Indian Nation. There is another in nearby Erie, PA.

The Seneca Nation has seen revenues at its casinos fall in the face of the new competition, and is using this argument to justify its’ refusal to keep paying the state.

Still, Niagara Falls Mayor Paul Dyster has tried to put a happy face on the disastrous development.

“Knowing Gov. Cuomo, I think he’s a big picture guy. He probably views this as an opportunity to try to establish a better overall system of relations between the state and Seneca Nation than has existed historically. There’s an opportunity for the governor and president to discuss a whole wide range of issues,’’ Dyster told a reporter.

During the 2009-2013 dispute — which sprung up over the state allowing slot machine-like devices to be installed at Batavia Downs and other race tracks — the Senecas withheld some $600 million in payments.

Throughout the four-year ordeal, Dyster maintained a Pollyanish faith the Cuomo would ride to the city’s rescue despite much evidence to the contrary. By the end of the four years, the city was nearly bankrupt.

After the settlement, Niagara Falls received $89 million, the bulk of which had been spent before it even arrived.

But despite Cuomo’s track record in dealing with the Senecas, Dyster expressed confidence that his hero would once again save the city.

“I know the state has a totally different read on the situation than the Senecas. I trust that the governor is going to work things out,’’ said Dyster.

In December, when the Senecas opened their tax free gas station and smoke shop on the 50-acres of prime Niagara Falls real estate that now constitutes a mini reservation in the heart of the tourist district, Cuomo remained silent.

It’s mind boggling. How do you sign off of what is essentially a 10-year contract extension without specifying what the other party has to pay?

That’s exactly what Cuomo did, and yet Dyster still has trust and confidence.