Niagara Falls Mayor Robert Restaino believes that if he can get taxpayer money to build his Centennial Park project, there will be significant economic opportunities for the City of Niagara Falls. According to his published plans, Centennial Park will be an arena with a parking ramp and other features. Restaino anticipates the arena will host “sporting events, concerts, indoor/outdoor gatherings, and youth-centered activities.”

Since Centennial Park, if it is built, will be built 100 percent at taxpayer expense, the public must be informed and have a say.

In this series, we will examine this plan in a measured way to see how realistic Restaino’s objectives are.

The Questionable Choice of Location

One of the most significant aspects in Restaino’s quest to build Centennial Park is the land he selected to build it on.

He did not undertake a site location study before settling on the site. The standard practice for government projects (and most private development) is to have experts evaluate the economic feasibility and practicality of a project at potential locations. Restaino selected the location himself. He says the sacrifices he asks the people of Niagara Falls to make to build his plan on the location he chose will bring sufficient economic gains to the city that it will be worth it. This is the subject of our investigation.

Restaino chose to build his arena on 10 acres of land fronting on John Daley Blvd, close to downtown and not on city-owned land.

It is part of a larger tract of land and the owners, Niagara Falls Redevelopment LLC (NFR), do not want to sell the 10 acres to the city.

NFR had its own plans for the land Restaino wants for the Centennial arena.

A Data Center Instead

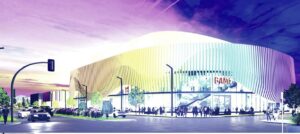

NFR wants to build the Niagara Digital Campus, where large corporate tenants can safely store important digital information — documents, customer data, and applications like emails, and websites – on computers and servers. NFR’s data center would attract tech companies because of the special systems the center offers that protect company information, such as power generators in case of electricity cuts, strong internet connections to send and receive data, temperature control systems to keep the equipment cool, and cyber and physical security to protect against theft or damage – which is essential for businesses that rely on digital activities.

Niagara Falls could be home to a giant computer hub for some of the world’s biggest tech companies.

NFR’s partnership with Urbacon, one of the leading developers and operators of data centers in North America, gives the project the expertise it needed. NFR’s owners, billionaire Manhattan brothers Howard and Edward Millstein, provide assurance of the financial security of this world-level undertaking.

The large-scale facility would employ about 550 people, including network engineers, systems administrators, database managers, cybersecurity experts, engineering, human resources, finance, management, customer support, security, and maintenance positions for the sprawling 60 plus acre facility.

Restaino Killed a Project in Process

Records show NFR was well into the approval process with the city when Mayor Restaino decided he wanted 10 acres at the front of the project, an area that provides street access, the entranceway and land for some critical buildings in the multi building data center for his Centennial arena.

The Reporter has criticized Restaino because he lied about NFR coming up with a data center plan only after he said he wanted the land for his arena. The Reporter examined city records that show NFR was involved with the Restaino administration in getting the project rolling, and that Restaino had participated in meetings with NFR executives to help get approvals for the data center in 2021. In early 2022, he made an about-face and decided he wanted the NFR property for his arena.

Restaino is not the first mayor to lie to the public. We understand why he lied. He wanted to make it seem that NFR was not serious about building a digital center, and therefore, he was not killing this giant economic development project, but dismissing it as “unreal.”

Documents show NFR had plans at city hall for the data center four months before Restaino made his first public statement that he wanted land in the middle of the proposed data center.

Eminent Domain

In America, the government cannot take someone’s land without paying. By law, a mayor can declare a public purpose for land that he claims is higher and more important than what the private landowners plan, and he can go to court and use a process called eminent domain to take your land.

The law does not question who knows what is best for the land, a mayor, who wants to build a $150 million taxpayer-funded arena, or a private landowner, who wants to build a $1.5 billion data center that would bring some of the biggest companies in the world to Niagara Falls.

The law presumes the mayor knows best, which may or may not be true. The law does not consider that NFR’s was planning to invest $1.5 billion, none of it taxpayer money, or that it was to be 10 times the size of the Restaino arena. Nor does the law consider that the Niagara Data Center would employ 10 times the people at higher wages than the Restaino arena. Or that arenas usually employ only a few full-time people and use part-time people on the days of events. On most days, an arena sits empty.

Though, by law, the mayor has the right to stop the data center by declaring a public purpose for the land, he can’t just steal the land. The city’s taxpayers must pay for NFR’s land. As for the price, the courts consider what the land is worth, and one of the factors is economic. Another factor is the economic loss to the owners, including the fact that Restaino by taking 10 acres broke up NFR’s larger project by taking the frontage.

The law creates a situation where a mayor can take the land for good or poor purpose and leave the taxpayers to foot the bill as the court determines the value of the property.

Arenas Lose Money

No one says the Restaino arena will not have some public benefit. It may. Restaino knows that arenas do not make money. But he claims that the economic development that comes from events at his arena with the spill over – people who come for a concert or sporting event who spend money at local businesses – will more than offset the cost of the arena.

The Restaino arena, like arenas everywhere, will operate at a loss estimated to be between $200,000 and million dollars each year, But Restaino claims that the city will see an improvement in financial health from the spill over for the events he hopes to attract.

Taxpayers Will Pay a Premium for NFR Land

Though Restaino seems to have won the legal right to take the property, the courts will decide how much taxpayers must pay NFR. That battle will go on for years.

The lawyers Restaino hired from Buffalo have already charged taxpayers a certain sum. Restaino does not want to reveal how much he has already spent in legal fees to win the right to take the land. The Buffalo law firm of Hodgson Russ will charge far more in legal fees to establish the final price in court.

Taxpayers will need to make a significant down payment–about $10 million at the time the city takes the land. Unfortunately, the city does not have the money to even make the down payment. Restaino has proposed borrowing money and paying it back annually by cutting back on street repairs and other city services for 20 years to budget for the down payment on land he singularly decided to take.

Keep in mind that Restaino does not know where the taxpayer money will come from to build the arena. He does not know where the money will come to buy the land and he’s keeping it secret from the council and the public how much he is spending on attorneys.

City-Owned Property Might Be an Alternative

This secrecy and high expense might seem more kosher if Restaino had considered other properties, including a city-owned property, that would not cost taxpayers any money to purchase.

IA city-owned lot on Third and Niagara is in the center of the Niagara Falls Heritage Path identified for development in a 2021 Downtown Niagara Falls Development Study adopted by the State of New York and the USA Niagara Development Corporation.

The city could save up to $30 million on the land if Restaino settled on a property the city already owns. No street would have to go unfixed.

I do not state that Restaino has a political grudge against NFR to explain this seemingly inexplicable obsession with a particular piece of land that will cost so much more and blocks a serious economic development project.

I do not say he is headstrong and must have his way – rule or ruin. Let us assume he is motivated by genuine belief that his arena in only this location will uplift the city – enough to offset the cost of the land, the cost of building the arena and maintaining it, and offset the loss in taxes and employment from killing a $1.5 billion data center.

I do say that if he reconsiders locating his arena on city land, the data center might still be built. Then, if he relocates his plan for the arena to city-owned land, and if Restaino can get the taxpayer money to build the arena, the city might have both.

This has been called the two-project solution.

Closer to City Businesses

The city owned site on Niagara Street is suitable for an arena, and for reasons we will discuss, is actually better for an arena than NFR’s land, if we take Restaino at his word: that the purpose of the arena is to bring economic development to the area.

The city-owned property is closer to the local businesses Restaino wants to help with the arena. The city would not have to purchase the land.

The city land has an adjacent city-owned parking ramp, so taxpayers will save another $30 million – of the estimated $150 million arena cost. The NFR’s land has no parking and will require taxpayers to build a parking ramp for the arena.

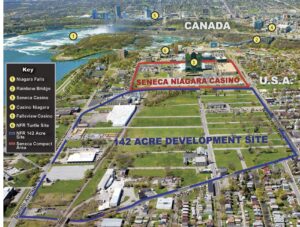

Another downside of taking NFR’s land for an arena is that visitors leave the arena and consider spending money after the event. They will have to pass through the Seneca nation and their array of businesses, including the casino, before they could get to the city businesses Restaino wants to help.

From the treetops of NFR’s land we can see the beneficiary of the mayor’s arena plans – the Seneca Nation and its businesses.

The Senecas have a steep advantage over city businesses, because they pay no state, property, or sales tax, while local Niagara Falls’ businesses pay high state and city taxes. By building the arena on NFR’s land, adjacent to the Seneca businesses, Restaino is handing the Seneca’s one more advantage in an already lopsided contest that has seen the Seneca’s wipe out many competing businesses, most recently gas stations.

The desire to favor the Seneca Nation is hard to understand. Restaino does not govern the Seneca Nation.

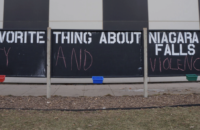

Restaino wrote in his arena proposal “When tourists fail to connect with the rest of Niagara Falls, including its shops, restaurants, and services, an enormous opportunity is missed.”

An arena built at the NFR location will help those who visit the arena to connect with the Seneca Nation not city business.

Who Will Use It?

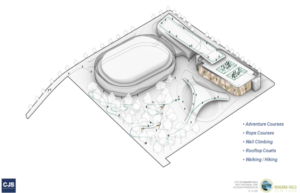

Restaino calls his enterprise an “Event Campus” and the events he anticipates are sporting events, concerts, indoor/outdoor gatherings, and youth-centered activities.

However, there is no significant sports team that needs an arena and Restaino has not identified any team that says they would use the arena if it is built. As for concerts, it will compete with others in the area which are better facilities.

There is an excellent possibility that just like the last mayor’s monument to his ego – the train station – the Restaino arena may be empty almost all the time. Taxpayers foot the bill for an oversized and always empty train station at a cost of around $200,000 per year.

It is true that Restaino has included gimmicks such as making the parking ramp walls a rock climbing wall and on the roof of the ramp selling beer. He has spoken of an ice-skating rink, a water feature, and zip-lining all to be done on the very small remaining two or three acres of land left from the 10 acres after the arena and parking lot are built. None of these are attractions in and of themselves and climbing the walls of a five-story parking ramp, having a few beers, and climbing down sounds dangerous.

In our next report we will examine Restaino’s comment:

“As the City continues to see a consistent number of visitors, the population and workforce development opportunities have shown a net loss, according to the 2020 Census.”

We will examine why the data center will provide far more workforce development opportunities than the arena.

Restaino has blocked a project that will provide 550 full time jobs without taxpayer funding to build an arena that will not provide a dozen full time jobs, while, at the same time, he talks about “workforce development opportunities.”

The part time jobs afforded by concerts and events sporadically through the year will not be high paid and not come anywhere close to the economic boom that will occur if the city ventures into the burgeoning tech business.

While it is possible that Restaino may fund his arena, is it wise to kill a real workforce development project when there are other locations that his arena could be built?

In our next in the series we will explore this further.