What were they thinking?

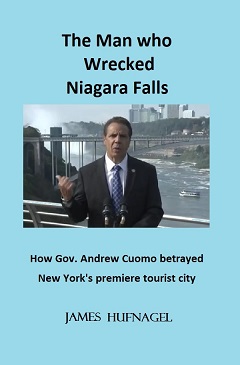

Back in 2002, when the state of New York, under the leadership of then Gov. George Pataki, handed 50 prime acres of downtown Niagara Falls real estate to the Seneca Nation of Indians to settle the Grand Island land claim and allow the Seneca to open a tax free casino and hotel resort here, what was the logic?

Today, as dwindling casino revenues bite into the measly 25 percent of the slot machine take that Albany graciously allows the city to keep in return for police and fire protection, infrastructure and other amenities, and the Seneca recently announcing the opening of a tax free gasoline station and smoke shop to be opened downtown, many here are wondering how the powers that were could have entered into such a bad deal.

It was easy.

“This has been a long and difficult haul but it’s worth it,” Gov. George Pataki said when the casino opened. “When you look at what has happened all around the borders of New York state, every time casinos have opened, they have attracted hundreds of millions of dollars … and created tens of thousands of jobs.”

On a local level, there was guarded optimism.

‘’It’ll work, as long as they keep the politicians out of it,’’ said the late Flo Acotto, whose Press Box restaurant across Niagara Street from the casino was eventually bankrupted by its’ opening. ‘’They’d mess up a one-car funeral.’’

Former mayor Irene Elia, along with the entire city Council, had been left out completely of the negotiations between the state and the Seneca. Still, she wanted to make it appear as though she had shown some initiative and chimed in.

“It’s been a long time coming,” Elia enthusiastically told reporters.

Former state Sen. George Maziarz said he was mostly concerned about how the city would use the multimillion dollar windfall it would receive as a result of the casino opening.

“Let’s look at the revenue as a source for funding economic development programs,” Maziarz said. “We’ve given the city lots of money in the past and it hasn’t been used well.”

In addition to the direct payments to the city, one of the major selling points of the Seneca casino was the “spinoff” that would occur throughout the distressed neighborhood where it is located. Thousands of casino employees would want to live close by work, it was said, and new housing would be needed, along with stores, churches and possibly even a new elementary school.

Today, more than a decade after the casino opened, the neighborhoods surrounding it remain more blighted than ever. And the recent announcement by the Seneca that a new, tax free gas station and smoke shop on the former site of the Niagara Street Pizza Hut will endanger the already precarious existence of the gas station and convenience stores located near the casino.

What were they thinking?

When the Seneca Niagara Casino opened, tour buses arrived every 15 minutes or half hour to drop of gamblers from Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York cities such as Rochester and Syracuse.

Today, those places have their own casinos or casinos easier to reach, and the tour buses have become a rarity. A quick visit to the city’s former convention center, gifted to the Seneca by the state for use as the casino, will reveal that the vast majority of gamblers pressing the slot machine buttons are Niagara County residents.

The loss of the convention center itself has had an incalculable impact on the fiber of the city. Now the city makes do with a small, state operated “conference center,” big enough to host large weddings or minor league boxing events.

Had the local share of the Seneca casino cash been spent on economic development, as was originally intended, perhaps its existence could be justified. Instead, for most of its run, Niagara Falls Mayor Paul Dyster used the money to plug holes in his bloated annual budgets and stage ego tripping non-events such as the Hard Rock Café concert series and the disastrous Holiday Market.

The Hard Rock concerts are particularly informative, as more than $700,000 in casino cash was directed toward them. In Los Angeles, California, the Hard Rock on Hollywood Boulevard features live entertainment seven nights a week and the residents of that fair city aren’t forced to underwrite any of the cost.

When the Seneca Niagara Casino opened in 2003, it was hailed as the beginning of a revival that would see the city flourish in the new millennium. In the years since, countless businesses have folded and as many as 10,000 residents have fled, seeking greener pastures.

It stands as one of many thought provoking examples that have, in recent years, prompted many here to ask the question:

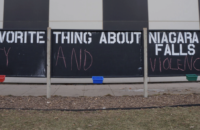

What were they thinking?