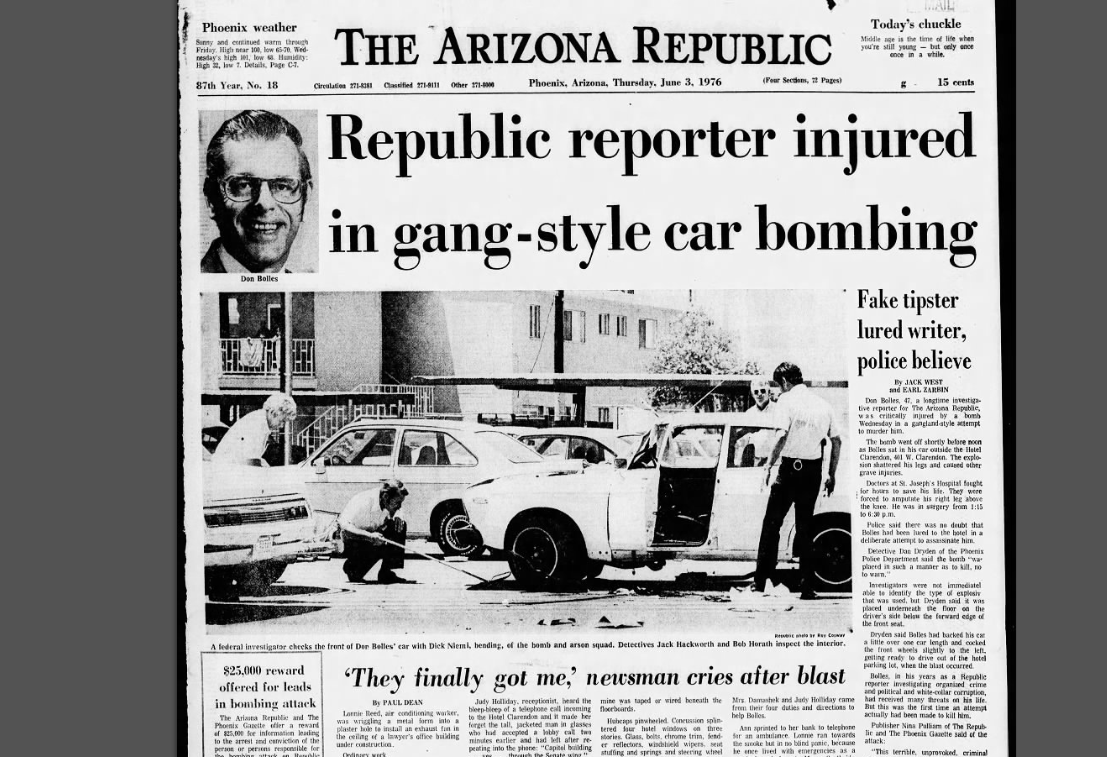

Before it was known as Delaware North, the global Buffalo-based concessioner called itself Emprise. A reporter at the time who relentlessly investigated the company and its business practices, Don Bolles, was murdered in a car bombing in 1976.

In 1972, the House Select Committee on Crime held hearings concerning Emprise’s connections with organized crime figures. Around this time, Emprise and six individuals were convicted of concealing ownership of the Frontier Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. As a result of the conviction, Emprise’s dog racing operations in Arizona were placed under the legal authority of a trustee appointed by the Arizona State Racing Commission.

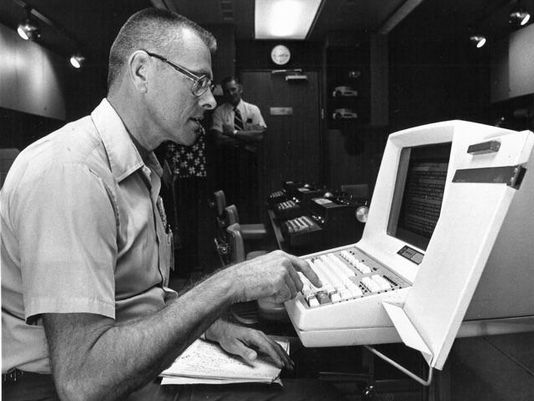

Bolles was investigating Emprise at the time of his death. His reputation for unrelenting investigative reporting of influence peddling, bribery, and land fraud was renowned.

On June 2, 1976, Bolles left behind a short note in his office typewriter explaining he would meet with an informant and be back about around 1:30 p.m. The source promised information on a land deal involving top state politicians – and possibly even the mob.

Bolles arrived at the hotel and waited several minutes in the lobby before a call was received for Bolles at the front desk. That conversation lasted only a few minutes, before he exited the hotel. His car was parked the adjacent parking lot just south of the hotel.

Bolles started the car. After moving no more than a few feet, a remote detonated explosive consisting of six sticks of dynamite attached to the underbelly of the car just under the driver’s seat exploded. The bombing shattered his lower body, opened the driver’s door, and left him mortally wounded while half outside the vehicle. Both legs and one arm were amputated over a ten-day stay in St. Joseph’s Hospital. He died on the eleventh day, June 13.

When found in the parking lot, his last words included “John Adamson”, “Emprise” and “Mafia.” The note that he left by his typewriter read, “John Adamson. Lobby at 11:15. Clarendon House. 4th + Clarendon.”

On October 20, 1976, Maricopa County District Attorney Donald Harris is quoted in the San Francisco Examiner asserting, that conspiracy by “the country club set” was more likely than mafia involvement. “The mob doesn’t kill cops and reporters. This is not a Mafia case.”

Bolles, 47, wrote frequently about land fraud and was the investigative reporter at The Arizona Republic tasked with covering state politics. His investigations resulted in the passage of legislation opening ‘blind trusts’ to public scrutiny.

Emprise, now Delaware North, was heavily invested in horse and dog racing. Bolles had written many articles about the company.

Bolles identified John Harvey Adamson by photograph while hospitalized. Adamson’s former lawyer, Mickey Clifton informed the police of Adamson’s involvement in the bombing. Adamson purchased the electronics for two bombs with a girlfriend in San Diego. Police found the electronics for the bomb in his apartment. During trial it was revealed that early in the day on June 2nd, Adamson went to the Arizona Republic parking lot, asking the attendant to identify Bolles’ car.

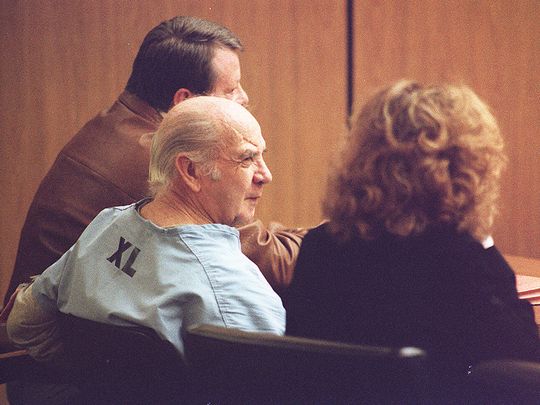

Adamson pleaded guilty in 1977; second-degree murder for building and planting the bomb. He also accused Phoenix contractor Max Dunlap. Dunlap was an associate of Kemper Marley, and allegedly ordered the hit as a favor to his friend. He alleged that James Robison, a plumber from Chandler, helped trigger the bomb. Police did not find evidence linking Marley to the crime. Dunlap and Robison were convicted of first-degree murder in 1976, but those were overturned in 1978.

James Robinson

Adamson refused to testify again. In 1980, he was charged and convicted of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to death, but the state courts overturned the penalty.

Robinson was re-charged in 1989, and re-tried and acquitted in 1993, but pleaded guilty to a charge of soliciting an act of criminal violence against Adamson. Dunlap was recharged in 1990 when Adamson agreed to testify again. He was found guilty of first-degree murder.

Adamson’s cooperation landed him a reduced sentence. He was released in 1996 and remained in witness protection until his death in 2002 at the age of 58. Both Dunlap and Robinson died in prison.

No connection between Emprise and Bolles’ death was discovered. In the coming months, this publication will revisit this case – and others.