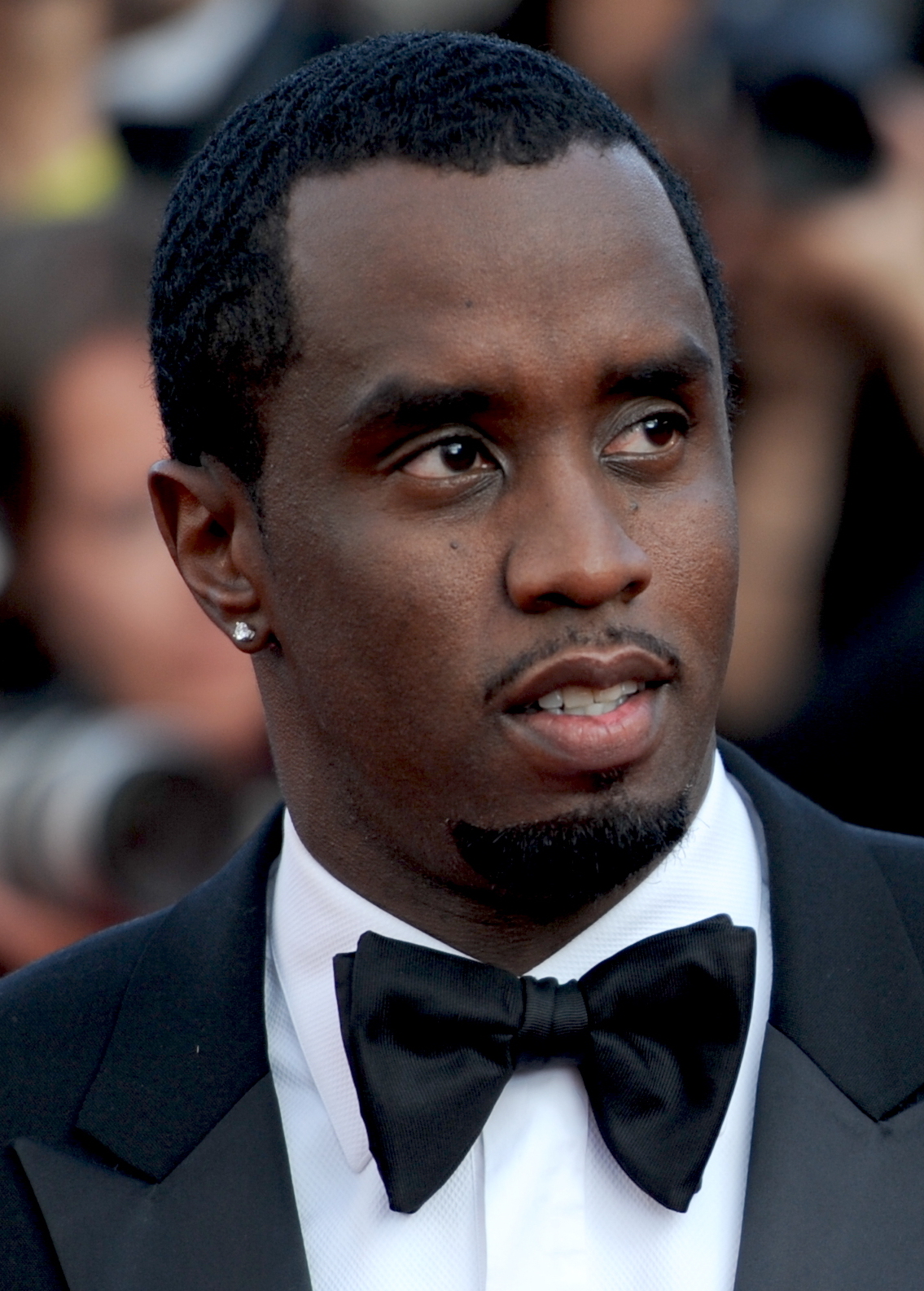

Sean “Diddy” Combs was acquitted of the most serious charges against him—racketeering and sex trafficking—after a grueling federal trial. Yet when he appeared before Judge Arun Subramanian last week for sentencing, those very allegations determined how long he would stay behind bars.

That’s not conjecture; it’s how federal sentencing works.

Under current guidelines, a judge may consider uncharged, unproven, or even acquitted conduct in determining punishment, so long as the allegations are deemed “proven” by a preponderance of the evidence—a far lower standard than “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

It’s one of the strangest paradoxes in modern justice: a jury says “not guilty,” but the judge can still sentence as if the defendant were guilty.

A Legal Loophole Turned Routine

The practice stems from a 1997 Supreme Court case, United States v. Watts, which held that acquitted conduct could be used in sentencing without violating the Double Jeopardy Clause. Congress never corrected it, and prosecutors learned to use it strategically—charge big, accept small, then let sentencing fill in the gaps.

In Combs’s case, prosecutors cited the same allegations of coercion and abuse that the jury explicitly rejected. They argued those accusations showed “pattern and intent,” convincing the court to impose a harsher sentence under the Mann Act.

It’s the legal equivalent of retrying the case after losing—a shadow verdict rendered not by twelve citizens, but by one robed official.

Punishment Without Conviction

This approach corrodes the very logic of the Sixth Amendment. It says a person can be exonerated in the eyes of the law yet punished for what the government believes he did. It erodes the moral authority of verdicts, invites prosecutorial overreach, and undermines public faith in due process.

Combs’s case is hardly unique. Federal inmates from white-collar executives to low-level drug offenders have watched their sentences balloon on the basis of conduct that was never proven or was expressly rejected by a jury.

The only difference here is visibility: because this defendant is famous, the public may finally notice what has long been hidden in plain sight.

The Call for Reform

Several members of Congress, from Senators Dick Durbin to Mike Lee, have introduced bipartisan legislation to ban this practice. The Prohibiting Punishment of Acquitted Conduct Act has languished in committee for years—ignored precisely because it challenges judicial convenience and prosecutorial leverage. With the current climate focusing on the appearances of judicial overreach and weaponization, perhaps this will now be taken more seriously.

If Combs’s sentencing becomes the catalyst for renewed debate, perhaps something good can come from this spectacle. The issue is not whether he deserves mercy or punishment; it’s whether anyone should be punished for conduct a jury refused to convict on.

In a time when faith in justice is collapsing, this simple principle should unite us:

If you’re not guilty, you shouldn’t be sentenced as if you were.