Please click the link below to subscribe to a FREE PDF version of each print edition of the Niagara Reporter

http://eepurl.com/dnsYM9

Director of Community Development, Code Enforcement, and now City Attorney? Not so fast. The last one requires a law license.

By: Nicholas D. D’Angelo, Attorney at Law

Analysis

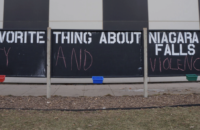

Director of Community Development and Code Enforcement Seth Piccirillo was recently quoted in an editorial, written in the Niagara Gazette, where he criticized the Niagara Falls Housing Court. In particular, Piccirillo said the court lacks a sense of “urgency” and has been “too lenient” on offenders.

To support their claim, the anonymous author quotes the following statistics:

“In an analysis covering February to May of this year, Piccirillo’s office found the city’s department of code enforcement delivered 485 citations to Niagara Falls Housing Court, with 92% of those cases being adjourned by the court.”

The author, however, is not being entirely honest with you.

First and foremost, it is important to understand how this process. A case originates when code enforcement sends a letter to the homeowner who is not in compliance with the code. The homeowner is then given at least thirty (30) days to remedy the problem. If, after that period, the problem persists, than the City moves forward with filing papers with the court. The Defendant then receives a summons in the mail with a court date that was signed by a judge. Upon appearing in court, a Defendant then negotiates with the city prosecutor.

There is absolutely no involvement by the District Attorney’s Office. It is purely the City of Niagara Falls.

Second, a Defendant has an absolute right to request an adjournment. Once the request is made in court by the Defendant, the burden then shifts to the Complainant, which in this case would be the City of Niagara Falls, to object. If there is no objection from the City Prosecutor, who appears to represent the interests of code enforcement, than the judge is likely to grant the adjournment. However, if there is an objection the judge would hear argument for why and then make a decision.

In the statistics referenced above there seems to be one key number missing. That number is the percentage that the City Prosecutor, the “Complainant,” objected to a Defendant’s adjournment request.

That number, in fact, is zero.

Third, there are legitimate reasons to grant adjournments. Some examples include

- Personal reasons such as illness of a party, family member or witness

- A Defendant is working and cannot appear

- Unavailability of a key witness

- Disclosure issues

- Settlement discussions

- Need to obtain legal counsel

- Counsel not available

- Good faith efforts to obtain information necessary for a hearing

- That the Defendant is working on fixing their violation

I am in no way saying that all requests for adjournments are meritorious, but why would the City Prosecutor object to an adjournment while people are making efforts to remedy their violations? Why would the judge? The answer is they wouldn’t.

The editorial concludes by stating, “for the sake of improving the overall condition and image of the city, the housing court should have a greater sense of urgency when it comes to punishing those who are contributing to the decay of the Falls and, in some cases, have been doing so now for many years.”

This quote represents a grave misunderstanding of the role a court plays in such proceedings. It is not the job of a judge to have an “urgency” for anything other than upholding the law, protecting the due process rights of defendants, and remaining impartial in all cases before them.

It would be wildly inappropriate for a judge to preside over a criminal court with the goal of putting repeat offenders in jail before he even hears their case!

The same goes for a judge presiding over housing court. A judge cannot preside over a court with the goal of “improving the overall condition and image of the city” as the editorial suggests because that would mean he or she is implicitly biased against the Defendant.

Despite Piccirillo wanting a more streamline, assembly line type of housing court model where each Defendant goes to court, receives a fine, and leaves, that is not how due process works. Fortunately for the residents of Niagara Falls, all City Court Judges understand this as well.