Despite some recent bad publicity, including an embarrassing black-spill in the Niagara Gorge last summer, there seems to have been dramatic improvements at the Niagara Falls Water Authority.

The Reporter has learned that two recently appointed board members have changed the way the authority is run, largely by taking a hands-on approach to its management.

The Niagara Falls Water Authority is an independent authority run by a five-member board appointed by the Niagara Falls Mayor, the Niagara Falls Council, the NYS Assembly, the NYS State Senate and the NYS Governor.

The Water Board was created in 2002 and assumed control of the city’s water and sewer treatment from the city under the administration of Mayor Irene Elia.

During its 16 year history, this may be the first time board members have become active in day-to-day management. It has resulted in a series of surprising changes in both the culture and outcomes of an authority long known as a bureaucratic wasteland.

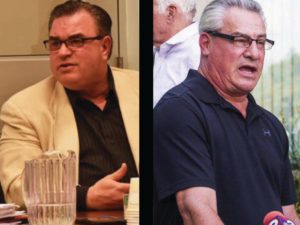

The two board members – the latest to be appointed – are Nick Forster – appointed by the Niagara Falls City Council in Jan. 2017, and Dan O’Callaghan, who is chairman, appointed by Mayor Paul Dyster in March 2017.

The other three members are Albany appointees – not active in management. They are: Gretchen Leffler [Governor] Colleen Larkin [Senate] Renae Kimble [Assembly]

O’Callaghan has had considerable experience in water lines and plumbing. He was the superintendent when the water plant was built.

Forster, who is also the Niagara County Democratic Party Chairman, said when he first came on board, he was asked to vote on a $9 million expenditure.

“I received the resolution, 10 minutes before I was expected to vote. Obviously I voted ‘no’,” he said.

He was also confronted with resolutions to approve extensions of the contract for the former executive director, Paul Drof, and other members of the administrative team – to 2020.

Forster knew he needed to make changes. Drof and his team were not reappointed.

The board appointed a new executive director in Rolfe Porter, a former Cleveland Ohio deputy commissioner of water who also worked at Buffalo as a chief engineer.

He was hired at $91,000. It was a cut from Drof’s salary, which was $119,000.

A Change in Culture

Forster recalls that the first thing he did was to change a rule of the ethics code that prohibited board members from speaking to union employees of the water board.

Forster found it stunning that the board – which is charged with the management and control of the water authority could only speak to management.

“The very first thing I did was have general counsel strike the language to allow members of the water board to speak to the employees,” said Forster. “When we look at when the problems began, I suspect it was when someone allowed language into the code of ethics that prohibited the governing board from talking to employees.

“How do you find problems out, if you can’t talk to employees? How do you have your fingers on the pulse, if you can only talk to the bosses? That was the tilting point.”

O’Callaghan said that he and Forster have talked to almost every one of the 114 employees. He said employees often asked him questions.

“I have done almost everything they do,” O’Callaghan said. “They come to me to ask for advice on how to manpower certain things.”

After they changed administrative personnel, and started talking to employees, they soon found much that was wrong or neglected:

- Thirty previous grievances

- Numerous violations of collective bargaining

- Civil service employees out of compliance

- Mail unopened from regulatory agencies for as long as three years

“That was the beginning of our understanding that we were in for a lot more than we originally imagined,” said Forster.

The two board members found another shocking item. For the two prior years, there was almost $1.9 million in overtime.

But there was no monitoring of overtime. It was on the honor system. There were no time clocks. An employee would simply turn his own time in.

One man, with a base pay of $55,000, made $148,000 — nearly $100,000 in overtime. A secretary got $40,000 in overtime, doubling her pay.

It was suspicious. Leaks seem to invariably occur on Friday nights. They would be fixed on overtime.

“That was how it was structured. That was why there was $1.9 million in overtime,” O’Callaghan said. “There were leaks that were probably called in on Tuesday and they would hold them until the weekend to get overtime.”

Forster went further suggesting that he believed some of the weekend overtime calls were fictitious.

When they started monitoring overtime, 12 people retired in three months.

“We cut overtime in the first year to $500,000 by monitoring it.”

Other accomplishments:

When they started in 2017, 68 percent of water being pumped was lost mostly because of leaks throughout the city.

The water board fixed a record number of leaks [35 leaks since Dec. 15] They were repaired during regular hours: i.e. more leaks fixed with less overtime.

“We believe the lost water is down to the middle 40s or better,” Forster said. “As we started fixing all these leaks, the loss of water started going down. We know what leaves the plant and we know what we bill.”

There is also no backlog of leaks, the board members say.

Another surprising item they found was that, out of the city’s 2500 fire hydrants, 152 did not work.

In nine months they put over 100 hydrants back in service.

“We are working on it every day, “ Forster said. “My father was fire chief in Niagara Falls for 16 years. He would have never put up with that many hydrants out.”

Next in our series on the Niagara Falls Water Board: New equipment, new contracts, new services for rate payers – and testing for the quality of water.