BY JAMES HUFNAGEL

How SEQRA works: Do not pass Go, Do not collect $200, Go Directly to Type II or a “negative declaration”, discounting public opinion and environmental considerations.

The State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) of 1978 was in tended to serve as a vehicle for citizen participation and government accountability with regards to decisions impacting the environment. Unfortunately, not only has the Act failed to live up to its original promise for greater democratization of environmental decision making, but certain state and local political leaders have turned SEQRA on its head, using it as a tool for obfuscation and delay.

On January 1, 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), requiring actions proposed by federal agencies that might affect the environment to undergo an evaluation process. NEPA was the logical successor to the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts (also created during those heady environmental days: the Endangered Species Act and the Environmental Protection Agency), and for 40 years has served as a model for laws here and inter- nationally that seek to ensure environmental considerations are not excluded from govern- mental decision-making processes.

SEQRA was enacted as New York State’s mirror statute of NEPA to ensure local and state compliance with a formal environmental review structure. According to the state Dept. of Environmental Conservation (DEC), the Act “requires all state and local government agencies to consider environmental impacts equally with social and economic factors during discretionary decision making. This means these agencies must assess the environmental significance of all actions they have discretion to approve, fund or directly undertake.”

Some examples of activities which may be subject to SEQRA review include construction projects such as shopping centers, roads, dams and residential developments, planning activities attendant to land use or district formation, and adoption of government rules, regulations, procedures and policies with respect to local zoning and planning, wetlands protection, public health regulations and handling of toxic wastes.

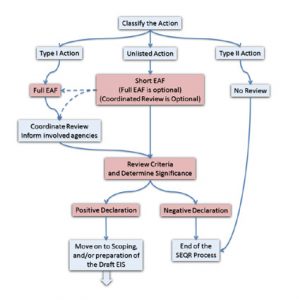

Briefly, this is how SEQRA is supposed to work. Before a government entity can commence implementation of or grant approval for any of the above “actions”, as the legislation calls them, an Environmental Assessment (EA) must be prepared pursuant to a “SEQRA Determination” which categorizes the action as Type I (projects likely subject to SEQRA, requiring complete review), Type II (not subject to SEQRA) or Unlisted (probably not subject to SEQRA).

The EA form is simple, standard and downloadable from the DEC web site. If determined to be Type I, having potential environmental impacts, then further SEQRA review is triggered, and a resultant public scoping and preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement takes place, which may result in alterations to the proposed action towards the end of improving environmental outcomes.

Significantly, however, the DEC, which otherwise regulates everything from fishing, hunting and trapping licenses to Superfund sites, flood control and publication of a bird atlas, states that “The Legislature has made SEQR self-enforcing; that is, each agency of government is responsible to see that it meets its own obligations to comply, LOL!”

Actually, we added the “LOL!” That’s because these “self-enforcing” agencies have, as a result, arbitrarily classified certain local projects with potentially massive environment impacts “Type II”, exempting them from messy SEQRA public hearings and official comment.

For example, New York State Parks immunized from public scrutiny its $50 million Niagara Falls State Park Landscape Improvements plan which involved felling numerous mature trees on Goat Island, expanding parking lots and installing new street lights, drainage systems, trolley stops, toll booths, restrooms and a concessions plaza for Delaware North in the former nature preserve.

State Parks bulldozed over a Niagara River tributary that separates Three Sisters Islands from Goat Island, yet they claim that their Niagara Falls State Park “Landscape Improvements” plan doesn’t have environmental impacts.

“As for ‘SEQRA compliance,'” a State Parks spokesman told this newspaper, “State Parks reviewed each project prior to initiating the construction bidding process and classified them as Type II actions, meaning they do not require any environmental review under SEQRA…”

According to the DEC, “Segmentation of an action into components for individual review is contrary to the intent of SEQR,” so clearly State Parks is violating the law.

While State Parks also ignored SEQRA in its rush to build Maid of the Mist owner James Glynn’s new boatyard in the Niagara Gorge after he’d been kicked out of Canada for alleged corruption, and in the run-up to its aborted attempt to build a new Parks Police barracks on the gorge rim, it’s successfully delaying north Robert Moses Parkway removal by conjuring an exhaustive, full, multi-year SEQRA review, the same way the NYS Dept. of Transportation is impeding efforts to remove Buffalo’s Skyway.

“DEC has no authority to review the implementation of SEQR by other agencies,” the agency continues, “in other words, there are no “SEQR Police.”

This may come as a shock to the bureaucrats at DEC, but there are SEQR police. They’re also known as the “public”, and a handful of them are presently suing Buffalo’s City Council and Planning Board in State Supreme Court over a planned apartment building on the Buffalo waterfront. Despite concerns about the proximity of nature preserves, recreational resources, aesthetics of an isolated glass tower on the shoreline and the fact that it will sit on a landfill, the city rated it “Type II”.

Spotted Bee-balm (top) and Culver’s Root (bottom), just two examples of rare and threatened species on the site of a proposed apartment complex on the Buffalo Outer Harbor shoreline next to the Greenway Nature Trail. State environmental laws were ignored so that the project can be rushed to completion.