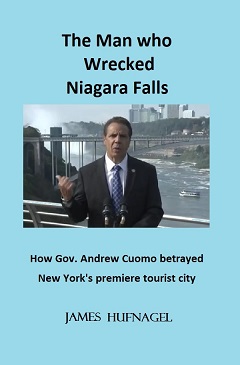

Two cities share the mighty natural wonder of Niagara Falls, but they differ in many ways, and the stark reality is the city north of the border, Niagara Falls,

Ontario, is light years ahead of the city on the American side of the falls, Niagara Falls, N. Y, and the differences are more than just population although the

Canadian city has close to 100,000 residents, more than double Niagara Falls, N. Y., which is steadily losing people.

Let’s begin by looking at the Canadian city famous for the iconic Niagara Falls, which attracts millions of tourists with attractions like boat tours, observation towers, casinos, and entertainment on Clifton Hill. It offers panoramic views of the Horseshoe Falls and is a major tourist destination with a vibrant atmosphere and provides natural beauty and nearby historic sites.

Niagara Falls, Ontario has evolved into a globally competitive destination with momentum, scale, and institutional follow-through, while on the U. S. side, that is not the case. And the reason is not geography, ambition, or even resources. It is execution.

The population reveals the first hard truth. With a population of close to 100,00, the Canadian city of Niagara Falls, the city north of the border, continues to grow. That scale supports a broader tax base, deeper labor pool, stronger housing demand, and the fiscal capacity to maintain and modernize infrastructure.

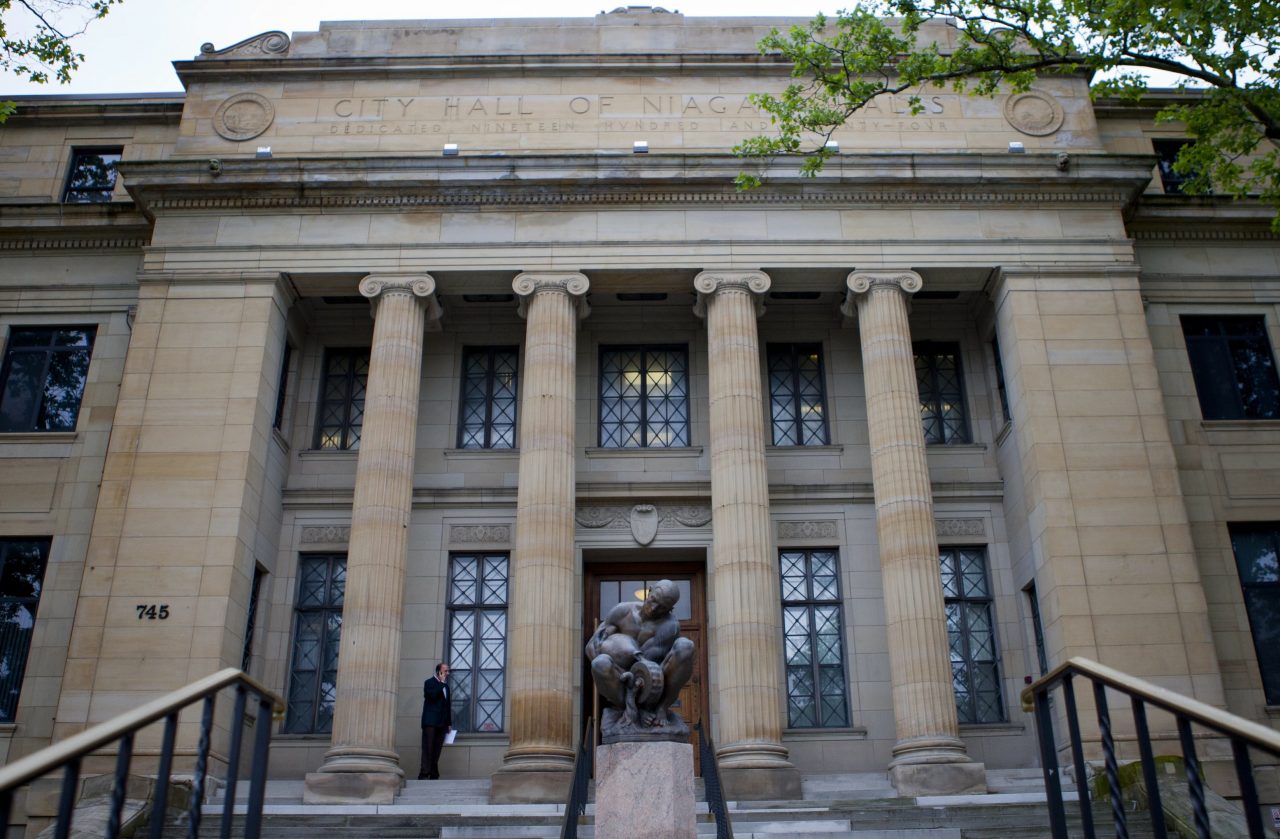

While Niagara Falls, N. Y., continues to try and prop up population numbers, the truth is that among those who actually underwrite projects—developers, lenders, utilities, and operators—the accepted reality is different. The effective, service- supporting population is closer to 40,000 and shrinking. School enrollment,

housing vacancy, work force participation, and infrastructure utilization all confirm it.

Investors do not finance aspirational narratives. They financial reality, not a Centennial Park project that the mayor is still looking for $200 million from the state to build, an ask that he continues to make with no positive response. A miracle that is not reality.

Tourism numbers appear to tell a more optimistic story but volume without capture is not success.

Canada has built a high-capture tourism economy. Hotels, attractions, dining, entertainment and gaming are clustered and walkable. Visitors stay overnight, spend repeatedly, and generate tax revenue that is reinvested back into the destination. The system compounds.

On the American side, the story is different. Visitors often arrive, take photos, and leave the same day. The city bears the cost of housing millions while capturing only fraction of the economic benefit. For a shrinking city, the imbalance is destabilizing.

Ideas are abundant, like pushing to extending and unifying the park footprint, an old idea that is still around and being talked about now. It may seem a logical step but the delay is the reality.

While the Canadian side consistently reinvests tourism revenues and delivers projects on predictable timelines, the U. S. side debates structure, jurisdiction, and responsibility. Each year of delay forfeits compounding benefits. Translation: momentum stalled, confidence eroded.

Projects on the U. S. side that enjoy widespread support often move slowly or unevenly. Momentum resets with political cycles. Capital responds accordingly:

Investors demand higher returns, shorter commitments, or they choose other markets—often overseas. This is not ideology; it is math.

Ontario’s advantage is not simply funding. It is continuity. Decisions survive elections. Capital investments are sequenced. Progress compounds. Niagara Falls, New York is not uniquely broken. It is emblematic.

Across the U. S., cities struggle to convert world-class assets into sustained economic engines—not because they lack ideas, but because they lack execution discipline. Niagara Falls, N. Y., simply makes the problem visible on a global scale.

Trying to match Canada’s skyline misses the point. The real challenge is rebuilding trust in the American delivery system. That requires a different playbook:

• prioritize execution over announcements.

• harden investor confidence frameworks so that development rights survive political change.

• stop relying on tourism alone; must work to build parallel, year-round economic engines.

• measure success not by press releases but by compounding outcomes: more overnight stays, higher private reinvestment, rising workforce participation, and

visible delivery.

The call to action is to fix the execution gap. That means fewer studies, fewer delays, and far more accountability. Until then, America and Niagara Falls, N. Y. will continue to admire its greatest assets while others monetize them better.

The waterfall is not the problem. The system is.