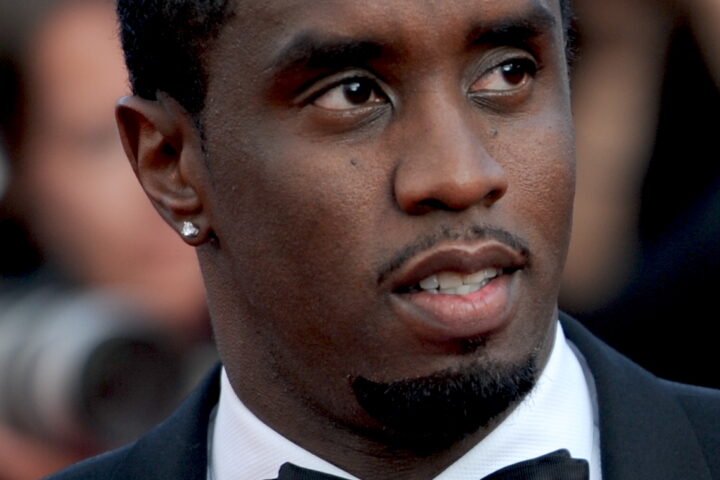

The prosecution of Carlos Watson, founder and CEO of the embattled media startup Ozy Media, has unfolded more like a made-for-TV drama than a fair and measured judicial proceeding. A case that should have raised red flags for its procedural flaws, lack of clear victims, and roots in startup culture norms instead became a media feeding frenzy—driven, in part, by sensationalist reporting and, arguably, judicial bias.

At the heart of the government’s case was the accusation that Watson defrauded investors and lenders by misrepresenting Ozy’s performance, reach, and key partnerships. Prosecutors painted a picture of a media company built on lies—a “house of cards,” they claimed, echoing language we’ve heard before in the fall of other startups. But unlike cases where financial loss or clear victimhood was evident, Watson’s situation stood apart. There were no injured parties clamoring for justice. No investors crying foul. In fact, many remained publicly supportive.

The tactics Watson was accused of—optimistic projections, image management, and strategic embellishment—are not unique to Ozy. They are, in many respects, part and parcel of the startup ecosystem. Founders from Silicon Valley to Brooklyn know the game: early-stage companies must pitch big visions to secure funding and press. If Watson’s actions constitute criminal fraud, then a large portion of the startup world is potentially prosecutable.

Judge Eric Komittee: Questions of Judicial Impartiality

Adding to the controversy was the role of Judge Eric Komittee, who presided over the case. Komittee’s background includes tenure at powerful institutions with deep ties to the financial elite, raising concerns about whether he could remain impartial in a case rooted in media narratives and financial innovation. Throughout the proceedings, defense attorneys raised objections to rulings they claimed consistently favored the prosecution—from pretrial motions to evidentiary decisions.

These concerns were magnified by Komittee’s dismissiveness toward arguments that Watson was being selectively prosecuted and scapegoated. When a judge brings personal bias, even unconsciously, into a high-profile case, it undermines public trust in the judiciary.

Ben Smith, the New York Times, and the Media Mob

Perhaps the most influential force in Watson’s downfall was not a judge or a prosecutor, but the media itself. A 2021 exposé by then-New York Times columnist Ben Smith cast a long shadow over Ozy Media. The article, which detailed an infamous conference call where an Ozy executive allegedly impersonated a YouTube representative to impress potential investors, became a defining moment in the public perception of Watson.

But the reporting, while dramatic, lacked nuance. Smith framed the call as evidence of a con, but failed to contextualize it within startup pressure-cooker tactics or to explore the murkiness of intent. From that point on, Watson was no longer seen as a daring entrepreneur, but as a grifter. Other outlets quickly followed suit, echoing and escalating the allegations without deeper investigation. The coverage didn’t just inform public opinion—it helped shape the case itself.

More troubling, however, is the question of whether Smith had a conflict of interest that should have disqualified him from reporting on Ozy at all. At the time he published the damning article, Smith reportedly had ties to a venture that had previously expressed interest in acquiring Ozy. If true, this raises serious ethical concerns—not only about Smith’s motivations, but about the New York Times’ decision to publish his piece without disclosing any potential conflicts. It’s fair to ask: was this journalism, or a strategic takedown?

In a moment when the boundaries between media, venture capital, and influence are increasingly porous, the Times’ failure to scrutinize the optics—or even the ethics—of Smith’s position is deeply irresponsible. The article became the accelerant that ignited Watson’s reputational downfall and ultimately led to his prosecution.

This was not a case of Ponzi schemes or pillaged pensions. No one lost their life savings. No employees were left destitute. Investors in Ozy were, for the most part, sophisticated players in the venture capital space. Yet the Justice Department pursued Watson with the zeal usually reserved for cases of massive consumer fraud or organized crime. In fact, the biggest investors on Ozy were Watson’s own family, and his sister addressed the court rejecting any charges of fraud, deception or malintent.

Legal scholars have noted procedural issues throughout the prosecution—rushed filings, questionable discovery practices, and a clear inconsistency in how the law was applied. Defense attorneys attempted to raise these flaws, but in the media and in court, their voices were drowned out.

A Cautionary Tale—and a Presidential Rebuke

The Carlos Watson case raises troubling questions about the criminalization of startup culture, the role of media in steering justice, and the integrity of the judiciary. At a time when innovation is often built on optimism and perception, the line between vision and fraud is blurry at best.

Watson may not be a perfect figure, but his trial was far from a perfect example of justice. When judges exhibit bias, when the press fans the flames of public outrage, and when the legal system punishes cultural norms selectively, it’s not just one man who suffers—it’s trust in the entire system.

That’s why, in a bold and symbolic move, President Donald Trump commuted Carlos Watson’s sentence, signaling that enough was enough. It was more than an act of clemency—it was a clear message to prosecutors, judges, and media conglomerates alike: weaponized justice, trial by media, and ideologically motivated prosecutions will not be tolerated in a country that claims to value fairness and the rule of law.

In commuting Watson’s sentence, President Trump didn’t just rescue one entrepreneur from a broken system—he put the system itself on notice.