By Frank Parlato

The land fight between Niagara Falls Mayor Robert Restaino and Niagara Falls Redevelopment LLC (NFR), a privately owned corporation headed by Manhattan developer Howard Milstein, is an extraordinary matter and deserves consideration by all Americans interested in government reach or overreach, property rights, and taxation.

Mayor Restaino’s Ambitions

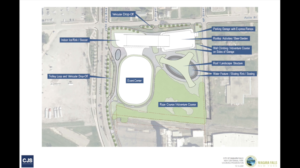

Mayor Restaino, elected mayor of a small city – some 47,000 people, down from 102,000 sixty-five years ago – wants ten acres of land owned by the aforementioned NFR. He claims he wants the land – 10 acres with a street address of 907 Falls Street, for the good people of Niagara Falls and for the “public purpose” of an arena, which would be, according to plans, both indoor and outdoor, with a seating capacity of about 7000.

Of all the possible places where the mayor might build an arena, he and he alone chose this location. He did no site selection study to determine if this is the best or even the only place to build an arena. Mayor Restaino also did not do a feasibility study to determine if the ailing, struggling, population-losing city, one of the poorest in the nation, could benefit from an arena. He is ruling by fiat. By gut. By intuition.

The Clash of Plans

He determined he wanted an arena. He says, without evidence, it will be transformative because it will extend the tourist season. This may or may not be true. But Robert Restaino believes it so much that he is willing to fight at taxpayer expense with billionaire owners of the 10 acres, NFR, Milstein, and his partners.

The fight is occasioned because NFR also has plans for the 10 acres. Ten acres is the entranceway – the street access to a project it has in mind – an AI digital data center. The estimated cost of the NFR project is $1.5 billion, which is precisely 10 times the cost Restaino says his arena will cost taxpayers.

A signal difference between NFR and the mayor’s plan is that the $1.5 billion is private money. No taxpayer in the city, county, state, or nation will have to pay to build this AI data center. On the other hand, if it is built, the arena will require the city, the county, the state, and possibly taxpayers across the nation (if there is federal funding) to pay for it.

The Financial Burden

It is an oddity of Restaino’s plan that, besides not having done a feasibility or site selection study, as he has more than causally admitted, he does not have the taxpayer funding to build his arena. Not yet. He says he is pretty sure he can get financing if he gets the land – if he takes the land in a fight with NFR.

To be clear, Mayor Restaino does not own the 10 acres. The city does not own it. NFR owns the land. NFR had plans to develop it along with another 60 acres of contiguous land to build a $1.5 billion data center. Companies in the tech field will rent space there because the Niagara Digital Campus can provide them with what they need to store and utilize massive amounts of data.

Both projects want the same land. NFR needs it, or there is no project. It is its street entranceway and part of the campus. Though it is unfunded, Restiano wants the same ten acres for his arena. No study has been made on whether it is the right land or whether, once built, anyone will ever use it. But he wants it, and he has started the fight.

The Eminent Domain Action

Over two years ago, Restaino initiated an eminent domain action. Eminent domain allows the government to seize private property for public use, provided the owner receives just compensation. NFR intends to develop a $1.5 billion AI data center on the land, creating 550 jobs. The loss of the project also needs to be considered when determining the just compensation taxpayers will have to pay NFR for the 10 acres – the loss of the $1.5 billion project.

The cost of Restaino taking the land by government power for an arena he has neither planned nor funded will be a cost unto itself – over and above the cost of building the $150 million arena.

Mayor Restaino has engaged the law firm of Hodgson Russ to manage the eminent domain proceedings, led by eminent domain attorney expert Daniel Spitzer. The cost to taxpayers will be hundreds of thousands or millions in legal fees, and the court will determine the price of the land.

It might be $20 million or $40 million that the city will have to pay to force the sale of ten acres of NFR land to build an arena. Mayor Restaino does not have the money to buy land. He does not yet even have the down payment. He has floated the idea of cutting back on street repair and demolition of blighted houses for the next 20 years to make the down payment of $10 million. But the reaction was bad.

He pulled back on that idea and shifted to floating an idea of borrowing money from investors through a municipal bond.

A Legal and Financial Quagmire

The man who wants 10 acres of land he does not own, who is using government power to take it from a private company, a man who has no money to build the arena, has plunged the city into a legal fight against NFR, which has all the money in the world to fight it – and fight over the price of ten acres, which is planned as the gateway to its 60-acre $1.5 billion AI data center project.

One of the stunning elements of Restaino’s arena plan is that he has no one to use the arena – no anchor tenant. It is slightly less than “build it, and they will come.” The arena’s success was predicated on securing a major anchor tenant, such as a professional or semi-professional sports team. To date, Restaino has not secured an anchor tenant. To find a tenant to justify his quixotic dream, he has entered into discussions with junior hockey leagues, which have not yet resulted in any agreements.

Earlier studies, which Restaino has never quoted, have indicated that without an anchor tenant, the arena could operate at an annual loss of $500,000 – that is, of course, not counting the cost of buying the land or building the arena – just the operating costs for taxpayers to pay annually.

Shifting Expectations

But with his outreach to junior hockey, Mayor Restaino’s arena project has transitioned from an ambitious event campus with the promise of a major sports anchor tenant to the humiliating prospect of an arena for youth and amateur sports. So Restaino, gone hunting for a sports team, went to Canada last month to speak with Ontario Hockey League (OHL) Commissioner Bryan Crawford. The OHL is a teenage league, a junior league, an amateur league of young hockey players, some of whom will make it into the NHL.

It is true that the OHL has expressed interest in U.S. expansion but has not identified Niagara Falls, New York, as part of that expansion. But a seemingly desperate Restaino, who faces sharp criticism for what is increasingly looking like a bizarre and stupid, perhaps vanity project, now tenders that he has a belief that an OHL team will act as an economic catalyst and save his arena idea, or justify it at least. To build an arena for a team you don’t have – a junior league team.

Restaino now says he wants to build a 7,000-seat arena for OHL games for a team he doesn’t have. But even if he did have the team, it is not well reasoned. The OHL average attendance for markets like Niagara Falls is about 2,000 per game. That will look mighty empty in a 7,000-seat arena.

The nearby OHL Niagara IceDogs in St. Catharines, Ontario, averaged 3,300 fans in a metropolitan area double the size of Niagara Falls. And 3,300 attendees in a 7,000-seat arena will also look empty. An oversized arena with half-empty seats creates negative perceptions. A half-empty arena gives the impression that the team lacks popularity. Empty seats diminish the excitement and energy of an event. Crowded venues create enthusiasm, which is hard to achieve in an oversized arena with empty seats. The arena is too big for OHL.

The NHL Shadow

Another reason is that building a $150 million arena for the possibility of an OHL team is a poor idea. While it is true that about 5 percent of the best players in OHL make it to the NHL so that hockey fans can see better quality players – there is already an NHL team here – the Buffalo Sabres, located just 20 miles away. The Sabres struggle with attendance, often filling less than 50% of their arena. The Sabres usually fare last in attendance of all NHL teams. It is hard to fathom how a junior hockey league team will be a winner in an oversized arena when the NHL team cannot even attract a full house.

A Mayor’s Misguided Vision

It is a sad thing, perhaps, to be a mayor, all puffed up with pride and bullheadedness. You have the name and think perhaps you have the power, so you railroad things. You do things without thinking. You use magical thinking. You spend taxpayer money, not your own, and you do what only a clown or fool would do: fight with a billionaire to take his land upon which he plans to build an actual project and think, just because you’re mayor of a tiny, nearly broke or broke city, you’re going to win.

You don’t have a plan. You don’t have the money. You are reduced to chasing junior sports teams. You are a zero, a real nobody, and it won’t end well. Not for you. Not for the people. But you don’t think of that.

Restaino said it all when he said, “If you have the site and you don’t get the money, you still have the site… the first step is getting the property.”

But you have more than the site if you get it. You stopped the progress of the site. You stopped 550 jobs. You stopped Niagara Falls from getting out of the doldrums and joining the 21st century – with AI tech.

Restaino wants to trade this for a vanity legacy, an arena for little league hockey. Something is wrong with the man.

But where do you go? How do you face the stupidity of your world and your plan? It ain’t easy to back down and say you were wrong.

In the end, one must wonder: how did it come to this? How did a mayor become so detached from reality that he would risk so much for a project that lacks any solid foundation?

Restaino is a cautionary tale about ambition unchecked by practicality, a reminder that leaders are sometimes as feverishly demented and recklessly foolish as the worst of us but in their case they carry the people down with them.

The community risks losing a significant investment in the AI data center, which promises to bring jobs and economic growth. Restaino’s arena project is unfunded and poorly planned, and will end up being a financial burden for the city and its taxpayers.

It’s time for him to find a way out. And it isn’t going to be little league hockey.