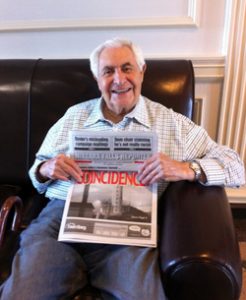

We recently had a conversation with Harvey Albond, a gentleman who has seen the ups and downs experienced by the city of Niagara Falls over a period spanning nearly the last six decades.

Mr. Albond, 88, served as City Manager for Niagara Falls for two terms, the first 1959-60, and again in 1985-86. He was also Director of Planning and Development for the city from 1967-1979, and not only has extensive and detailed recollections of the past, but passed along some insightful recommendations for the future.

Our conversation began with a discussion of the impact of hydropower on the city’s past prosperity, and how things changed after the Niagara Power Project at Lewiston, NY was completed and made operational in the early 1960’s. Prior to that, hydropower generated from the Niagara River was locally-owned, locally-controlled, and powered local industry.

“Industries were happy (before the Power Project), stated Albond in our interview, “but there was only one reason they were here – energy.”

Then things took a turn for the worse. Albond repeated the statistics that many are already painfully aware of – that the city has lost over 37,000 jobs since 1957, the year the Schoellkopf Power Plant, the private-sector forerunner of the state-owned and operated Power Project, collapsed into the Niagara Gorge, killing one and effectively ending the era of locally-produced, locally-distributed hydropower in the city of Niagara Falls.

That the burgeoning industry of the city of Niagara Falls simply fell victim to the overall “rust belt” syndrome that befell factories and manufacturing across a wide swath of the eastern and mid-western US, beginning in the late 1960’s, is, according to Harvey Albond, something of a myth.

“The industry of Niagara Falls was based on carbon products and electrochemicals, not rust belt industries related to automobile production,” he told us, “What’s more, the companies here were national and international in scope – operating predominantly out of older plant buildings. They were under no obligation to stay, and after the new arrangement with the state taking over the generation of hydropower, under no incentive to stay.”

“Industries left because they could not get answers from NYPA regarding how much hydropower was available, when it would be available and how much it would cost.”

According to the 1960 US Census, the city of Niagara Falls had a peak population of 101,000. That repeated the results of an earlier, special census undertaken by the city in 1957 that arrived at the same figure. “Everybody knew the city was bursting at the seams,” he recounted, “and more state aid was needed to accommodate the growth that was taking place.”

Unfortunately, the downward spiral had begun, and 5,000 jobs alone were lost while the NYPA Niagara Power Project was being built from 1957-1961. While the population of the city increased by an estimated 10,000 due to Power Project construction, that was offset by the job losses suffered in the aftermath of the Schoellkopf disaster.

Ironically, in an apparent case of the tail wagging the dog, many of the workers who toiled in the chemical plants of Niagara Falls came in daily from Buffalo and Erie County, quite different from today’s scenario where Buffalo is the apple of New York State’s eye, given the Buffalo Billion and the NYPA dollars that flow there courtesy of the Power Project’s 50-year relicensing and the Greenway.

Mr. Albond, who also served as a Niagara Region State Parks Commissioner until 2013, takes a dim view of the legacy of the Robert Moses, controversial namesake of the Power Project and its associated, detestable parkway.

“Robert Moses, in my opinion, deliberately diverted our power to benefit downstate NY interests,” he says, “Our bills are far too expensive for having all this power in our backyard.”

“In my opinion, we will not regain the industry of the 21st century without having access to local power… hydropower still holds the key to the 21st century”

When this interviewer brought up the fact that some 200 administrators who work at NYPA’s White Plains, NY headquarters enjoy $100,000+ salaries, Mr. Albond, with the uncharacteristic use of an expletive, exclaimed, “Hell, we have that here!”

Albond also shared insights on other topics such as tourism, and regionalism.

“Tourism was always regarded as secondary. Men would do it to moonlight – it was a seasonal phenomenon… It’s possible to expand tourism through trade shows and conventions – we might make it more attractive than going to Syracuse.”

“We need to become a metropolitan area. Unfortunately, the surrounding towns (Niagara, Wheatfield, Lewiston) don’t need us, like us or want us.”

“Spending money on tourism promotion is like hauling coal to Newcastle. Bed tax was originally to pay off bond debt on the convention center. Then state legislators redirected it to tourism promotion (without saying so, we took that to mean the NTCC).”