Parkway Redesign Funnels Tourists into Park, Bypassing City

By Frank Parlato

The pro-business management of the Niagara Falls State Park has done much to impoverish the city. Consider: The Niagara Falls State Park is the most visited state park in the United States with an estimated eight million annual visitors. Have you ever heard of a place that gets eight million visitors, every one of them with money in their pocket, that is broke? The reason for that is the state park tries to capture all the money from all eight million. This process began in the 70’s and continues to the present day. Across the river from our ghost town is a boom town with the same name. The difference being that their parks are open and integrate with the city. In order to get to their parks, tourists have to drive through the city.

The latest and perhaps the final plans for the Robert Moses Parkway, may look and sound like an improvement but it could further reduce tourism traffic to the city. In other words, what may be good for the state coffers may not be helpful to city business interests.

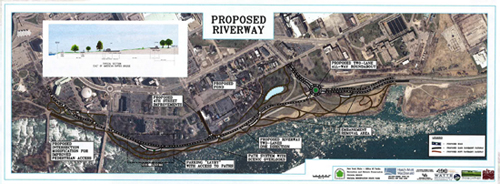

Here are the facts: The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation (Parks) has finalized its selection of a plan for the “South Segment of the Robert Moses Parkway,” the stretch of Parkway from John Daly Boulevard to the Rainbow Bridge in Niagara Falls.

Parks officials claim there were three alternatives for what to do with the parkway. And, in 2009, they fulfilled their legal requirement of having a public meeting and displaying the choice of plans at the Orin Lehman Visitor Center in the Niagara Falls State Park. At that time, more than 150 people came and spoke out mostly against what wound up being Parks’ preferred choice of the three plans, the option called “Riverway”.

The Riverway narrows the parkway to a two-lane, one-way road leading directly to the Park. At one end, it creates a traffic circle at the junction of Robert Moses Parkway and John Daly Boulevard, and at the other end, according to the plans presented at the Orin Lehman Visitor Center, it moves up the actual entrance for automobiles entering the park to the junction of the parkway and Old Falls Street.

Parks officials, couching the purpose of spending $20.3 million in what they term “park aesthetics,” say the Riverway option will allow a greater “appreciation of the Rapids” and will be in keeping with the original plans of Frederick Law Olmsted, the 19th century designer of the park who proposed that the park remain pristine and without commercial enterprises. The plan includes new pedestrian paths and a pond. So far, the state has only committed $5 million to the project.

The Riverway plan, however, is not primarily a plan of park design or landscaping, as park officials suggest, although it might be an improvement over the present parkway for people once inside the park. Visitors will enjoy slower road speeds and fewer obstructions to the river from embankments.

But make no mistake about it, the plan fundamentally serves to route more people directly into the park, with fewer chances for tourists to get distracted or diverted into the city before they get inside the park. It will serve to better separate and alienate the Niagara State Park from the city.

Still, why does it matter whether tourists go to the park first since everyone who comes to Niagara Falls ultimately winds up in the park to see the waterfalls anyway?

Millions of tourists - possibly as many as eight million - come to Niagara Falls annually, most of them during a short hundred-day summer season. The Niagara Falls State Park, counting both the Goat Island and Prospect Park areas, is perhaps 120 acres not counting water.

What Riverway does is help direct the maximum number of tourists quickly into the three paid parking lots inside the park. Presently, there is a paid parking lot in the Prospect Park portion with 300 spaces. There are two lots on Goat Island with 900 spaces.

Many acres of the park (especially noticeable in the limited-size Prospect Park section) have already been cleared of trees to make lots, and more acreage could be set aside to accommodate the hoped-for benefits of the Riverway plan.

Of course, the goal of Riverway – which might be called “Rove-away” since the hope is that tourists will not rove into the city – is economics.

Parks officials discovered that when tourists park in the city and walk to the park, State Parks loses not only parking revenue but concession and souvenir revenue. Even worse, tourists might not buy the State Park’s $33 Discovery Pass or ride the paid trolley service in the park.

And, since there are an abundance of stores and restaurants inside the park to accommodate every tourist who visits Niagara Falls, any money spent on restaurants or stores outside the park represents dollars lost for Albany.

The plan of the state park, since the introduction of the Robert Moses Parkway, and the subsequent building of paid parking lots and stores, has been to create a growing business enterprise.

Routing motorists along the Robert Moses Parkway serves to help them avoid the city and drive directly into the park, paying $10 for parking. Once there, the attractions are the Cave of the Winds ($11), Maid of the Mist ($15.50), Adventure Theater ($11), Discovery Center ($3) and Niagara Scenic Trolley ($2).

Then there is the Cave of the Winds Snack Bar, the Prospect Point Café, the Top of the Falls Restaurant, and numerous concession portables throughout the park. In fact, the Park even competes for weddings and banquets, where “the Park’s experienced culinary team is available to create the perfect menu for any occasion.”

I bet Olmsted never imagined the park would have an “experienced culinary team,” especially since his plan called for the prohibition of restaurants in the park in order to not compete with the city and to keep the environment surrounding the falls free of commercial endeavors.

As for stores, there is the Top of the Falls Gift Shop, the Cave of the Winds Gift Shop, the Prospect Point Gift Shop, and the Maid of the Mist gift shop.

Who needs to go to the city?

After an average four-hour stay, without a single advertisement in the park for any activity in the city, tourists leave, believing there is nothing else to do in Niagara Falls, NY and head for the bright lights of Canada.

The Niagara Falls State Park is designed to get people in and out, so they can open up more parking spaces on peak days. The business model is to have every dollar a tourist spends in Niagara Falls spent in the park alone, a goal which is often achieved and with which the Riverway plan will exponentially help.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the Riverway plan will help one of the biggest vendors in the park, James Glynn, owner of the Maid of the Mist. It will bring more traffic closer to his Comfort Inn Hotel and stores on Falls Street.

Considering Glynn’s ability to get state officials to work for goals that help his businesses even if it is a disadvantage to the public, perhaps a part of the decision to implement the Riverway plan might be intended to aid Glynn. If the park entrance is moved, his hotel and boutique stores will almost be an extension of the park, with the entrance moved to his doorstep.

Obviously, the State of New York could save millions by simply ending the Robert Moses Parkway at John Daly Boulevard, eliminating the entire Parkway inside the Park, eliminating the need for an expensive traffic circle. That would be more in keeping with Olmsted’s vision and cheaper for the taxpayers.

This alternative was never considered. The reason for this is spun, hypocritically, as concern for tourists on the one hand, and for some city businesses on the other hand.

From the Park’s own published plan: “One of the major concerns is that (removing the parkway) does not provide direct access [emphasis mine] to the State Park from the U.S. interstate system, which is how the majority of park visitors [happily, merrily, for the park] get to the park.

“It would change the travel patterns in the City which is likely to benefit some businesses at the expense of those at the opposite end of the park.”

In other words, if the Park did not get the business first, the businesses that are presently getting a few crumbs at one of the end will have to share half a loaf with a whole new string of businesses at the other end of the park that currently get nothing.

As far as the Riverway plan is concerned, there does not appear to be a public hearing, nor will an environmental impact statement be required to implement the plan. That does not mean it is a done deal.

One of the seven Commissioners of the Niagara State Park, Harvey Albond, opposes the plan and is calling for a special meeting of the Niagara Regional Commission to discuss this proposal.

For more information, or for the opportunity to express your opinion, the Reporter urges the public to attend the City Council Meeting, next Monday evening, January 22nd, where this topic will be discussed.